- Visibility 134 Views

- Downloads 28 Downloads

- DOI 10.18231/j.ijogr.2020.013

-

CrossMark

- Citation

An economic model to assess the value of triclosan-coated sutures in reducing the risk of surgical site infection in obstetrics and gynecological surgeries in India

- Author Details:

-

Nilesh Mahajan *

-

Reshmi Pillai

-

Hitesh Chopra

-

Ajay Grover

-

Ashish Kohli

Introduction

Surgical site infection (SSI) is one of the leading infection among healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), especially prevalent in low and middle-income countries (LMICs).[1] The incidence rates of SSIs in India are comparatively higher varying between 23-38%. In Telangana, the estimated SSIs for each condition (n=100) were 5% for clean, 58.3% for clean-contaminated, 85% for contaminated, and 66.6% for dirty wounds.[2] In a cohort study among obstetrics and gynecology patients, out of 1173 patients, 92 were affected with SSI. Thus, the cumulative incidence rate of SSI was 7.84% (95% CI, 6.30 – 9.38). The SSI rates were lower for obstetric surgeries compared to gynecological surgeries; 1.23% (95% CI 0.02 – 2.4) versus 10.37% (95% CI 8.32 – 12.43), respectively.[3] Another study reported out of 285 gynecological patients, 46% had SSI.[4]

Although there is a fewer incidence of SSI with obstetrics and gynecology surgery, patients suffering from SSI not only have to bear the additional cost due to extended hospital stay but also have to undergo pain and suffering due to delayed wound healing that increases the economic burden of a patient. In addition affects a nation’s economy.[5] A case-control study reported that from hospital-acquired bacteremia the maximum hospital stay was 22.9 days, significant intensive care unit stay was 11.3 days while mortality rate was 54%, and these costs may exceed INR 6,71,255 (US $14,818, cost converted from US dollars to INR using exchange rate of INR 45.30/USD as per the publication) for treatment.[6] Forty to sixty percent of SSI are manageable risk or non-manageable risk because bacterial adherence and biofilm formation on implanted sutures and suture materials become a nidus of infection causing acute exacerbations or dissemination.[7] Hence, suture materials coated with an antibacterial or antimicrobial agent such as triclosan have the potential to reduce the risk of SSIs or HAIs.[6]

Triclosan is a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent active against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. There are contrasting opinions regarding the use of triclosan-coated sutures (TCS). Recent studies involving several thousand patients showed that TCS or triclosan impregnated sutures can efficiently reduce SSIs[12], [11], [10], [9], [8] whereas, in contrast, a study involving 2546 patients suggests that TCS is inefficient in reducing SSI.[13] Furthermore, another study demonstrated higher incidences of SSI on the use of TCS (bioactive sutures).[14] However, WHO Guidelines (2018) have recommended the use of TCS irrespective of the type of surgery.[15] In this retrospective study, we accessed the incidences of SSI and the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of TCS based on decision-tree analytical model for obstetrics and gynecology (Ob/Gyn) practices for two surgical procedures, L-hysterectomy and C-section, in India.

Materials and methods

Literature search and data extraction

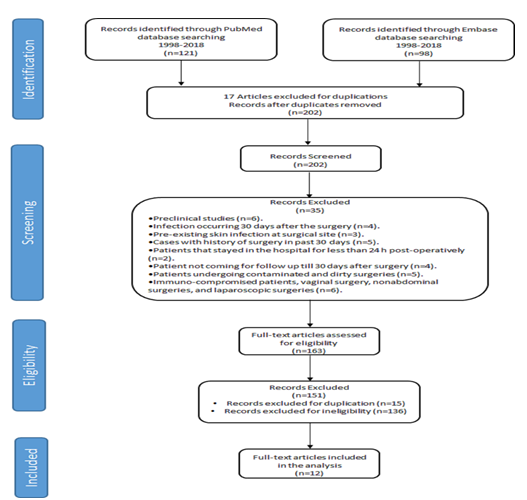

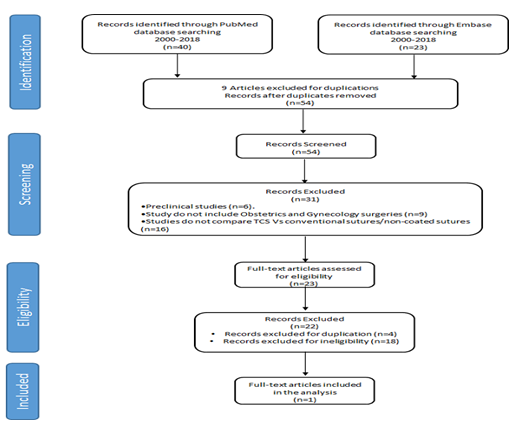

For both economic burden analysis of SSI in India and the efficacy of TCS vs NCS, we conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) of available evidence to gather epidemiologic and economic data pertaining to the occurrence of SSI from 1998-2018 ([Figure 1]) and the efficacy of TCS vs NCS from 2000-2018 ([Figure 2]). Evidence was gathered from prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs), comparative cohort studies, and high-quality systemic review. PubMed Medline and EMBASE indexed articles were searched using Mesh terms or Emtree, respectively, and free test terms such as SSIs, the incidence of SSI, efficacy and cost-effectiveness of TCS. Search criteria were defined by total number of patients undergoing surgery (N), number of patients developing SSI (n), and type of health care institute (private and public hospital). In this study, data extracted was from Indian studies for Ob/Gyn surgery that included two surgical procedures L-hysterectomy and C-section. For all publications, the SSI or surgery wounds were recorded as defined by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as clean, clean-contaminated, contaminated, and dirty.

Full papers were retrieved from accepted articles. Manual checking of references for relevant articles was performed. Data extraction was conducted by one reviewer and re-examined by others.

Cost Study

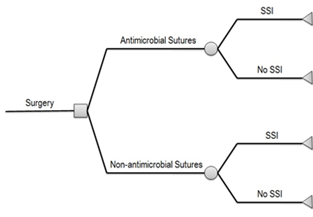

We conducted a cost study to assess costs associated with SSI. We determined the package cost of 1 C-Section and 1 L-hysterectomy procedure from 2 tertiary care hospitals (private and public hospital) in Mumbai, India. We also determined the cost associated in treating patients with and without SSI by obtaining and calculating cost information (refer section: cost analysis model for SSI). Further, we also calculated the difference in the cost of TCS vs NCS using a decision-tree model for the efficacy of TCS in SSI (refer section: cost analysis model for TCS vs NCS) ([Figure 3]).

Statistical Analysis

Cost analysis model

SSI

In the economic burden study, the SSI incidence (number of patients with SSI/total number of patients undergoing surgery expressed as the median, the range was calculated to determine incidence (expressed as a %) of SSI. This was supported with a cost study to obtain costs associated with SSI. The cost associated with treating patients with or without SSI was obtained from 2 tertiary care hospitals (one private and one public hospital) in Mumbai, India. In addition, the standard SSI treatment protocol for that hospital was obtained for analysis. To analyze, the cost of treatments of patients developing SSI with those without SSI following parameters were considered such as total cost of hospital stay for patients, total cost of surgical bundle (including surgeons, Operation Theater (OT), anesthetists, and bed charges), average total cost of antibiotic treatment, cost of procedures for management, pathology service costs, medical staff costs, and cost of intervention.

The SSI incidence data was combined with cost data to calculate the extra cost due to SSI. The cost difference in public and private hospital setting was calculated by combining the SSI incidence (%) with the total cost incurred by the patients with or without SSI. This helped us for the calculation of extra cost due to SSI per 100 surgeries performed that were specific to private and public hospital settings in India.

TCS vs NCS

In the TCS/NCS efficacy study, decision tree analysis model was designed, as shown in the Figure. 3 to compare the costs of TCS and NCS in surgical procedures. The decision tree analysis is the most widely used model which provide a framework for the calculation of the expected value of each available alternative.[16] In current study SSI incidence expressed as the proportion of patients developing SSI by the total number of patients was determined from SLR for the TCS and NCS group across Ob/Gyn (L-hysterectomy and C-section). Cost data for treating patients with or without SSI were calculated from the cost study. These costs were assigned as the payoff to different branches of the decision tree that enabled calculation of total costs associated with the use of TCS and NCS. Sensitivity analysis was performed to check the quality and reliability of given model and its prediction provides the understanding of how model variables react to input changes.[17] In this study the key inputs considered are the probability for developing SSI (or SSI risk), the efficacy of TCS, and cost of sutures. The calculation of cost savings using the decision tree model were based on the following assumptions: the cost of TCS and NCS was the same in private and public hospitals and the maximum retail price (MRP) was used for each suture; SSI incidences were assumed the same for private and public hospitals; efficacy of TCS was obtained from a literature study of Ob/Gyn surgery; and SSI incidences from literature sources for each surgical procedure (L-hysterectomy and C-section) represented the SSI incidences for the NCS arm of the decision tree model.

Results

Study identification

A total of 219 citations were screened manually for SSI and studies those did not include rates of SSI were excluded. After final review, 12 studies were included for analysis of SSI however for TCS vs NCS efficacy, only 1 study was included.

Included studies

Twelve out of 10 studies were prospective and 2 studies were descriptive ([Table 1]). The total number of patients included for SSI analysis were 13,847 ([Table 1]). For TCS vs NCS efficacy, only 1 study was available ([Table 1]). The total number of patients (n=284) were included in the TCS vs NCS efficacy study. The study compared Polyglactin 910 suture without triclosan coat (VICRYL) Vs Polyglactin 910 suture with triclosan coat (VICRYL Plus). Out of 12 studies, 11 studies followed CDC guidelines of wound infection and within a 30-day time frame following surgery. Wound infection guidelines were not available for 1 study.

| First author | Year | Study Design | Setting | Category |

| Bangal et al.1 | 2014 | Prospective observational | Tertiary care hospital in the rural area of central India | L-hysterectomy |

| Pathak et al.3 | 2017 | Prospective | Chandrikaben Rashmikant Gardi Hospital, Madhya Pradesh | L-hysterectomy C-section |

| De et al.21 | 2013 | Prospective | Lady Hardinge Medical College and Smt. Sucheta Kriplani Hospital, New Delhi | C-section |

| Priya K et al.19 | 2016 | Prospective | Meenakshi Medical College and Research Institute, Kanchpurum, Chennai | C-section |

| Dahiya et al.18 | 2016 | Prospective observational | Dr Baba Saheb Ambedkar Hospital, Rohini, New Delhi | C-section |

| Shah et al.18 | 2015 | Prospective observational | Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital and Medical Research Institute, Mumbai | L-hysterectomy |

| Chada et al.20 | 2017 | Prospective cross-sectional | Narayana Medical College and Hospital | C-section |

| Naphade and Patole27 | 2017 | Prospective longitudinal | Dr. Vasantrao Podar Medical College Hospital and Research Center, Nashik | L-hysterectomy |

| Sujatha and Sasikumari26 | 2017 | Descriptive | Sree Avittam Thirunal Hospital, Thiruvananthapuram | C-section |

| Swain25 | 2014 | Prospective descriptive | A tertiary teaching hospital in Odisha, SUM hospital | C-section |

| Vijayan et al.24 | 2016 | Descriptive | Tertiary care and teaching center, Dept of Ob/Gyn Government MCH, Kottayam, Kerala | C-section |

| Singh et al.23 | 2014 | Cohort prospective surveillance | 12 hospitals in 6 Indian cities | L-hysterectomy |

| Hara et al.22 | 2017 | Retrospective | - | TCS Vs NCS |

SSI Rate Analysis

We calculated the SSI incidence rate from Indian studies for 2 Ob/Gyn surgical procedures (C-section and L-hysterectomy). We used SSI incidence ranges (lowest to highest) ([Table 2]).

| Specialty | Surgical procedure | Low SSI Incidence (%) | Median SSI Incidence (%) | High SSI Incidence (%) |

| Ob/Gyn | C- Section | 3.77 | 7.94 | 24.2 |

| L-hysterectomy | 2.28 | 6.51 | 11.7 |

Efficacy Rate Analysis

Due to limitation of the number of studies, the analysis of efficacy rates of TCS (median and ranges) were calculated from 1 global study for Ob/Gyn surgical category and included in our study analysis ([Table 3]).

| Surgical Specialty | No. of studies | Efficacy of TCS vs NCS (median) | Upper end | Lower end |

| Ob/Gyn | 1 | 51% | 61%* | 41%* |

Cost analysis

Cost data were obtained for L-hysterectomy and C-section from both private and public hospitals. We have considered opportunity cost as loss of surgical package based on bed occupancy.

Decision tree analysis model presented in [Figure 3] was used to calculate the costs associated with the use of TCS and NCS. The difference in total cost for each suture type was represented as the model output.

For L-hysterectomy and C-section surgeries with TCS at private and public hospitals, at risk of SSI (41%, 51%, and 61%), cost savings were observed at all efficacy values. Cost savings were increased with an increase in SSI incidence and efficacy with the use of TCS (Table 4). Considering the introduction of Ayushman Bharat scheme for L-hysterectomy and C-section (surgical package cost of INR 9000), cost savings were observed across all SSI risk and efficacy levels.

| SSI incidences (%) | |||||||

| L-hysterectomies | C-section | ||||||

| Efficacy of TCS (%) | 2.28 | 6.51 | 11.7 | 3.77 | 7.94 | 24.2 | |

| Private Hospital | 41 | -132902 | -394313 | -715052 | -205508 | -441668 | -1362526 |

| 51 | -167269 | -492439 | -891406 | -257583 | -551344 | -1696800 | |

| 61 | -201635 | -590564 | -1067760 | -309658 | -661019 | -2031075 | |

| Public Hospital | 41 | -22390.3 | -78772.4 | -147950 | -25248 | -62023.7 | -205422 |

| 51 | -29802.6 | -99936.5 | -185987 | -33357.3 | -79102.6 | -257476 | |

| 61 | -37214.9 | -121100 | -224024 | -41466.5 | -96181.5 | -309531 |

We calculated the incremental cost of TCS suture (Cost of TCS-Cost of NCS)/Surgical package cost*100) for cesarean surgery. A private hospital the incremental cost was 0.1% and public hospital -0.89%. The incremental cost for L-hysterectomy surgery at private hospital was 0.1% whereas at public hospital was 0.4%. The cost savings (%) generated using TCS was greater than the incremental cost increase across all SSI incidences and TCS efficacy rates.

Sensitivity analysis

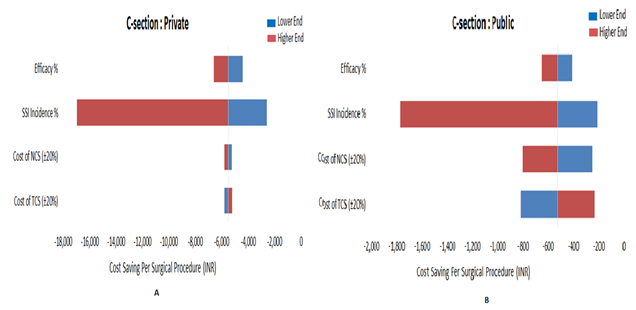

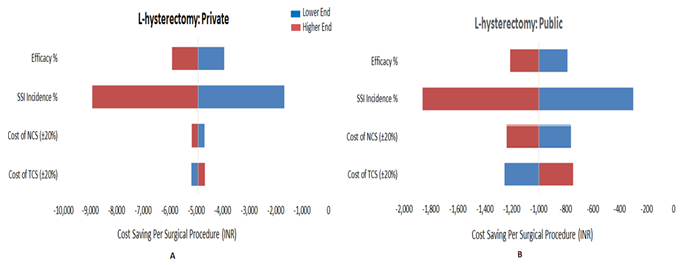

The results of one-way sensitivity analysis was further detailed using tornado plots, for C-section ([Figure 4]) and L-hysterectomy (Fig.5) Showing the impact of four independent variables; efficacy%, SSI incidences%, cost of NCS (±20%), and cost of TCS (±20%) on cost - saving per surgical procedure in private and public hospital. The most sensitive factor was SSI incidences followed by efficacy, cost of NCS, and cost of TCS. Among the individual variables, the least sensitive factor was cost of TCS.

On comparison of TCS with NCS, a base value cost savings for C-section for the private hospital was INR - 5513 ([Figure 4] A) and public hospital INR -791 ([Figure 4]B). For L-hysterectomy, a base value cost savings for a private hospital was INR -4924 ([Figure 5] A) and public hospital was INR -999 ([Figure 5]B). SSI incidence had the greatest impact on total cost saving. However, the literature study did not differentiate wound type as clean, clean-contaminated, contaminated, and dirty with respect to SSI.

Discussion

SSIs is a growing concern in developed and developing countries. In India, higher incidence of SSIs have been reported and the cost of treatment may exceed INR 6,71,255.[11] There are contrasting views on the use of TCS for SSI. A study, that included 7 RCTs encompassing 836 patients reported that the use of TCS is not beneficial.[28] whereas another study that included 17 RCTs involving 3720 individuals reported that the use of TCS is beneficial.[29] Furthermore, among three studies evaluating the effect of TCS on abdominal procedures.(20–22) Two studies showed no effect[31], [30] whereas one showed a substantial reduction in SSIs (35%-65%).[32] Due to contrasting opinion on the use of TCS for SSI, to our knowledge, we for the first time evaluated the efficacy and cost -effectiveness of TCS in obstetrics and gynecology patients, in India. This systematic review included a prospective,[19], [18], [3] prospective observational,[20], [33], [1] prospective cross-sectional,[21] prospective longitudinal,[22] descriptive,[25], [24], [23] and cohort prospective surveillance[26] studies for SSI, and a retrospective (double-glove)[27] study for TCS vs Non-TCS efficacy.

Our analysis showed a trend in cost-saving by the use of TCS which was directly proportional to efficacy. The cost savings generated for C-section for SSIs per 100 surgeries for similar incidences (3.77%, 7.94%, and 24.2%) at private hospital at low efficacy (41%) were INR 2,05,508; INR 4,41,668; and INR 13,62,526, and high efficacy (61%) were INR 3,09,657; INR 6,61,018; and INR 20,31,075, whereas at public hospital the cost savings at low efficacy (41%) were INR 25,248; INR 62,023; and INR 2,05,422, and high efficacy (61%) were INR 41,466; INR 96,181; and INR 3,09,530, respectively. Similarly, the cost-saving for L-hysterectomy for SSIs per 100 surgeries for similar incidences (2.28%, 6.51%, and 11.7%) at private hospital at low efficacy (41%) were INR 1,32,902; INR 3,94,313; and INR 7,15,052, and high efficacy (61%) were INR 2,01,635; INR 5,90,564; and INR 10,67,760 whereas at public hospital the cost-saving at low efficacy (41%) were INR 22,390; INR 78,772; and INR 1,47,950 and high efficacy (61%) were INR 37,214; INR 1,21,100; and INR 2,24,024. Depending on their efficacy, TCS may, in fact, save more costs per SSI prevented than many other interventions.

Several studies have reported the efficacy of TCS in different SSIs.[34] In addition, Hara et al, 2017 reported the efficacy of TCS using double-glove specifically in abdominal hysterectomy implicating that use of TCS in combination with double gloving were able to alleviate SSIs.[27] Our analysis showed that cost - saving generated at both public and private hospitals concluded the use of TCS is beneficial. Therefore, healthcare resources savings predicted by the decision-tree deterministic and stochastic cost model used in this study, suggest that antimicrobial sutures could be included in SSI surgical care bundles, which have been shown to reduce the risk of SSI.

The cost-saving generated by the use of TCS in private hospitals for both L-hysterectomy surgery and cesarean surgery was 47% whereas in public hospital the cost- saving was 35.84% for L-hysterectomy and 29.72% for cesarean surgery. A lower cost of coated-suture can generate even more cost savings, leading to an additional saving; the costs savings per C-section and L-hysterectomy increased linearly with increasing efficacy and with increasing SSI Incidence. Cost savings would decrease proportionately with higher-priced coated-sutures. The reasons for such a wide range in results are unclear and design limitations are to blame, for instance, small sample size and limited controls, varied incision closure methods, SSI definitions, incomplete data, or reporting biases.[26] To conclude, the results from our analysis are sensitive to the efficacy of TCS, however, additional studies are needed to establish the efficacy of such sutures and evaluate their benefits for surgeries with varied SSI rates.

Conclusion

The current study concludes the triclosan-coated suture was effective in reducing the risk for postoperative SSIs in a broad population of patients undergoing L-hysterectomy and C-section surgery. Our analysis showed a trend in cost-saving by the use of TCS was directly proportional to efficacy and it outweighs additional cost of lengthy hospital stay, antibiotic treatment and surgical procedure for management of SSI. T he use of TCS leads to better patient outcome with minimal or no SSI.

Source of funding

None.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- V B Bangal, S K Borawake, K K Shinde, S Gavhane. Study of Surgical Site Infections following Gynaecological Surgery at tertiary care teaching hospital in Rural India. Int J Biomed Res 2014. [Google Scholar]

- S M Patil, K S Kumar, K Rajesh. Surgical Site Infections in a Rural Hospital: A Prospective Study. IJSS J Surg 2016. [Google Scholar]

- A Pathak, K Mahadik, M B Swami, P K Roy, M Sharma, V K Mahadik. Incidence and risk factors for surgical site infections in obstetric and gynecological surgeries from a teaching hospital in rural India. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2017. [Google Scholar]

- S Bharatnur, V Agarwal. Surgical site infection among gynecological group: risk factors and postoperative effect. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol . [Google Scholar]

- A Arora, P Bharadwaj, H Chaturvedi, P Chowbey, S Gupta, D Leaper. A review of prevention of surgical site infections in Indian hospitals based on global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection. J Patient Saf Infect Control 2016. [Google Scholar]

- A Kothari, V Sagar, V Ahluwalia, B Pillai, M Madan. Costs associated with hospital-acquired bacteraemia in an Indian hospital: a case-control study. J Hosp Infect 2009. [Google Scholar]

- S Kathju, L Nistico, I Tower, L-A Lasko, P Stoodley. Bacterial biofilms on implanted suture material are a cause of surgical site infection. Surg Infect 2014. [Google Scholar]

- K Ichida, H Noda, R Kikugawa, F Hasegawa, T Obitsu, D Ishioka. Effect of triclosan-coated sutures on the incidence of surgical site infection after abdominal wall closure in gastroenterological surgery: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial in a single center. Surg 2018. [Google Scholar]

- N C Arslan, G Atasoy, T Altintas, C Terzi. Effect of triclosan-coated sutures on surgical site infections in pilonidal disease: prospective randomized study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2018. [Google Scholar]

- S S Samra, V Jagad, M Mahajan, M Randhawa, C Trehan. Impact of using triclosan-impregnated sutures on incidence of surgical site infection: a real world Indian study. Int Surg J 2018. [Google Scholar]

- M Aggarwal, A Kumar, P Pandove, B Anand. Triclosan coated polydiaxanone suture versus noncoated polydiaxanone suture in preventing surgical site infection in perforation peritonitis: a comparitive study. Int J Surg Med 2018. [Google Scholar]

- J Ruiz-Tovar, Alonso N, A Ochagavía, A Arroyo, C Llavero. Effect of the abdominal fascial closure with triclosan-coated sutures in fecal peritonitis, on surgical site infection, and evisceration: a retrospective multi-center study. Surg Infect 2018. [Google Scholar]

- A Sprowson, C Jensen, N Parsons, P Partington, K Emmerson, I Carluke. The effect of triclosan-coated sutures on the rate of surgical site infection after hip and knee arthroplasty: a double-blind randomized controlled trial of 2546 patients. Bone Jt J 2018. [Google Scholar]

- K Ravi, K Venkateshwara, - Venkanna. Incidence of Surgical Site Infections in Abdominal Wound Closure with Triclosan Coated Sutures. IOSR J Dent Med Sci . [Google Scholar]

- . World Health Organization. Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- A D Node. Decision trees. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- M Briš. . Sensitivity analysis as a managerial decision making tool 2007. [Google Scholar]

- S Shah, T Singhal, R Naik. A 4-year prospective study to determine the incidence and microbial etiology of surgical site infections at a private tertiary care hospital in Mumbai, India. Am J Infect Control 2015. [Google Scholar]

- K Priya, J G R, P Priya, M Muthulakshmi, K Raj, V.M S. Surgical Site Infection and Incidence of Mrsa Using Phenotypic and Genotypic Methods from Tertiary Care Hospital. J Dent Med Sci 2016. [Google Scholar]

- C K R Chada, J Kandati, M Ponugoti. A prospective study of surgical site infections in a tertiary care hospital. Int Surg J 2017. [Google Scholar]

- D De, S Saxena, G Mehta, R Yadav, R Dutta. Risk factor analysis and microbial etiology of surgical site infections following lower segment caesarean section. Int J Antibiot 2013. [Google Scholar]

- T Hara, A Miyoshi, A Tanaka, S Kanao, M Takeda, M Mimura. Can Triclosan-Coated Sutures and the Use of Double Gloves Reduce the Incidence of Surgical Site Infections?. J Clin Gynecol Obstet 2017. [Google Scholar]

- A Singh, S M Bartsch, R R Muder, B Y Lee. An economic model: value of antimicrobial-coated sutures to society, hospitals, and third-party payers in preventing abdominal surgical site infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014. [Google Scholar]

- C Vijayan, S Mohandas, A G Nath. Surgical site infection following cesarean section in a teaching hospital. Int J Sci Study3 2016. [Google Scholar]

- D Swain. A Study to Assess the Incidence and Risk factors of Surgical Site Infection following Caesarean Section in a Selected Hospital of Odisha. Indian J Surg Nurs 2014. [Google Scholar]

- T Sujatha, O Sasikumari. Prevalence and Microbial Etiology of Surgical Site Infections Following Major Abdominal Gynecologic Surgeries in a Tertiary Care Center. J Med Sci Clin Res 2017. [Google Scholar]

- S A Naphade, K Patole. Study of surgical site infections following gynaecological surgeries in a tertiary care hospital. MVP J Med Sci 2017. [Google Scholar]

- J Chang, Z Liao, M Lu, T Meng, W Han, C Ding. Systemic and local adipose tissue in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Z Wang, C Jiang, Y Cao, Y Ding. Systematic review and meta-analysis of triclosan-coated sutures for the prevention of surgical-site infection. Br J Surg 2013. [Google Scholar]

- J Baracs, O Huszár, S G Sajjadi, Ö P Horváth. Surgical site infections after abdominal closure in colorectal surgery using triclosan-coated absorbable suture (PDS Plus) vs. uncoated sutures (PDS II): a randomized multicenter study. Surg Infect 2011. [Google Scholar]

- C Mingmalairak, P Ungbhakorn, V Paocharoen. Efficacy of antimicrobial coating suture coated polyglactin 910 with tricosan (Vicryl plus) compared with polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) in reduced surgical site infection of appendicitis, double blind randomized control trial, preliminary safety report. Med J Med Assoc Thail 2009. [Google Scholar]

- T Nakamura, N Kashimura, T Noji, O Suzuki, Y Ambo, F Nakamura. Triclosan-coated sutures reduce the incidence of wound infections and the costs after colorectal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Surg 2013. [Google Scholar]

- P Dahiya, V Gupta, S Pundir, D Chawla. Study of Incidence and Risk Factors for Surgical Site Infection after Cesarean Section at First Referral Unit. Int J Contemp Med Res 2016. [Google Scholar]

- D Leaper, Edmiston Jr C, C Holy. Meta-analysis of the potential economic impact following introduction of absorbable antimicrobial sutures. Br J Surg 2017. [Google Scholar]

How to Cite This Article

Vancouver

Mahajan N, Pillai R, Chopra H, Grover A, Kohli A. An economic model to assess the value of triclosan-coated sutures in reducing the risk of surgical site infection in obstetrics and gynecological surgeries in India [Internet]. Indian J Obstet Gynecol Res. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 09];7(1):59-65. Available from: https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijogr.2020.013

APA

Mahajan, N., Pillai, R., Chopra, H., Grover, A., Kohli, A. (2025). An economic model to assess the value of triclosan-coated sutures in reducing the risk of surgical site infection in obstetrics and gynecological surgeries in India. Indian J Obstet Gynecol Res, 7(1), 59-65. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijogr.2020.013

MLA

Mahajan, Nilesh, Pillai, Reshmi, Chopra, Hitesh, Grover, Ajay, Kohli, Ashish. "An economic model to assess the value of triclosan-coated sutures in reducing the risk of surgical site infection in obstetrics and gynecological surgeries in India." Indian J Obstet Gynecol Res, vol. 7, no. 1, 2025, pp. 59-65. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijogr.2020.013

Chicago

Mahajan, N., Pillai, R., Chopra, H., Grover, A., Kohli, A.. "An economic model to assess the value of triclosan-coated sutures in reducing the risk of surgical site infection in obstetrics and gynecological surgeries in India." Indian J Obstet Gynecol Res 7, no. 1 (2025): 59-65. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijogr.2020.013