Introduction

Cervical pregnancy is the rarest form of ectopic pregnancies, with incidence varying from 1/1000 to 1/50,000 and associated with high morbidity and mortality.1 The occurrence of cervical pregnancy has increased in recent decades with the increasing use of assisted reproductive techniques, although the causes are not sufficiently described.2 Several risk factors associated with cervical ectopic pregnancy include use of intrauterine devices, history of abortions, local endometrial injury (prior cesarean delivery, uterine curettage etc.) and IVF treatment with embryo transfer. It is more commonly seen in Assisted Reproductive Techniques (ART) conceptions accounting for 0.1% of all IVF pregnancies and 3.7% of all IVF ectopic gestations.3 Most of the patients present with first trimester painless vaginal bleeding. Due to high vascularity of cervix, it becomes a suitable site for implantation of embryo. However, it is also extremely vulnerable to massive hemorrhage because of its suboptimal hemostatic mechanical capacity and insusceptibility to respond to uterotonic agents.

Ultrasound and rapid assay of serum human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) made diagnosis easier and more accurate. Different treatment methods have been used, but, due to rarity of this condition, there is lack of standard guidelines for its management. The diagnosis is generally late that prevents treatment through aspiration of the pregnancy without the occurrence of intense bleeding or the need for emergency hysterectomy. This article describes a rare clinical case of cervical ectopic pregnancy after IVF with ET, successfully treated with endocervical curettage after administration of PGF2 alpha analogue.

Case Report

A 32-year old female presented at our hospital for her first visit with episode of painless vaginal bleeding after undergoing her third IVF cycle with embryo transfer done and having 6 weeks amenorrhea. In her gynecological history, she underwent diagnostic laparoscopy with chromopertubation and ovarian cystotomy for primary infertility, followed by ovarian induction. She underwent 6 cycles of IUI which were unsuccessful. In her obstetric history, she had 2 missed abortion of which, first was spontaneous conception which ended up in evacuation and curettage twice for RPOC and second conception after 2nd IVF cycle and evacuation and curettage done. This followed by ovarian induction which was not fruitful so diagnostic dilation and curettage with Rubin’s test done, which was normal. She conceived in her 3rd IVF cycle after embryo transfer done at other centre. On presentation, she was hemodynamically stable. Abdominal palpation showed no signs of guarding. Pelvic examination was normal, cervix closed, uterus and bilateral adnexa were normal in size. She had mild motion tenderness in vaginal fornices area.

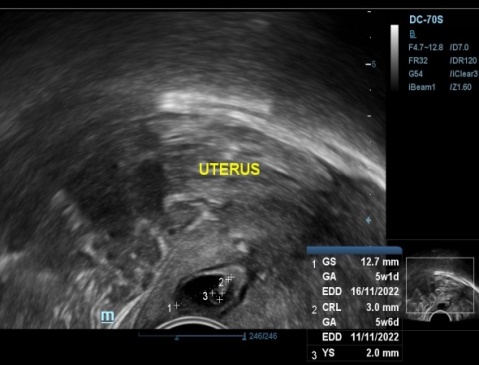

Transvaginal ultrasound revealed empty uterine cavity, with presence of gestational sac in cervical canal measuring 12.7mm, yolk sac and CRL measuring 3mm corresponding to gestational age of 5 weeks 6 days within cervical canal just below the level of internal os (Figure 1, Figure 2) Fetal cardiac activity was present with FHR of 106/min.(Figure 3) There was presence of peripheral and parietal neovascularization (Figure 4). Cervix was mild enlarged. Sliding sign absent. Her serum beta HCG report was 3725 mIu/ml. Patient was explained about the condition and risk associated with management. All routine investigations done which were normal. Following day, patient was admitted for dilatation and curettage after taking written informed consent for possibility of hysterectomy and blood transfusion beforehand in case of severe hemorrhage. Hysteroscopic removal with resectoscope trolley also kept prepared. Two units of blood preserved. PGF2 alpha analogue 250mcg intramuscular given 30 minutes before instumental removal. Under general anesthesia, after patient had been placed in lithotomy position, vagina was prepared with antiseptic solution.Per speculum showed en masse expulsion of product of conception, as fleshy mass at external os(Figure 5a)This mass removed by gentle tweezing by ovum forceps (Figure 5 b,c). Dilatation followed by curettage of cervical canal with blunt curette done(Figure 5 d,e). Aspiration of remaining products done using suction cannula to ensure complete evacuation. There was no intraoperative hemorrhage. Prophylactically, hemocoagulase solution soaked gauze was inserted in the canal to achieve hemostasis (Figure 5 f). Vaginal pad inserted. Vaginal hemostasis revision performed after the procedure. Gauze and pad removed after 6 hrs which were minimally blood stained. There was no bleeding on removal. Her hospital stay was uneventful and she was discharged the same day in good general condition. Cervical tissue removed was sent for histopathological examination which confirmed gestational changes and presence of chorionic villi and trophoblastic cells suggestive of Product of conception and negative for gestational trophoblastic disease (Figure 6).

Transvaginal ultrasonography identifying the ectopic pregnancy presenting gestational sac in cervix and empty uterine cavity.

TVS showing cervical ectopic pregnancy with 2-D and 3-D image showing peripheral Cardiac activity neovascularization.

Discussion

The implantation of fertilized eggs in the cervix is often unstable, and most patients with cervical pregnancy abort within 20 weeks of pregnancy.4 There are profuse blood vessels around the gestational sac, and the embryo will increase its vitality as the gestational age increases, which increases the risk of miscarriage and hemorrhage in patients with cervical pregnancy.5 Early diagnosis and management remain cornerstone in successful conservative management of cervical ectopic pregnancy. The basic goals in its management include: reduce blood loss, removal of cervical gestational tissue and spare fertility. Conservative approaches in cervical pregnancies are, however, possible for up to 10 to 12 weeks of pregnancy, as with advanced pregnancy the trophoblastic tissue infiltrates deeply into the cervical wall.

The literature reports 12 cases of exclusive cervical ectopic pregnancy after IVF-ET.6 The etiology of cervical gestation after IVF-ET is poorly understood. It is believed to be related to the aggravation of contractions of the junctional zone of the uterus in the luteal phase as a result of the elevation of progesterone, producing a similar effect like on the tubal motility. There are chances that the uterine fundus region stimulation caused by the probe during Embryo transfer also changes the contractility of the junctional zone. Also, women who presented with other forms of ectopic pregnancy had a higher peak of estradiol after ET.7 Different authors accept these hypotheses, although they warn that women who undergo assisted reproduction procedures and present as cervical ectopic pregnancy often have other recognized risk factors, such as previous uterine instrumentation, uterine and cervical anatomical abnormalities, Asherman's syndrome, uterine fibrosis, chronic endometritis or endometrial atrophy.8

Ultrasonography has been very useful in reducing maternal mortality in cases of cervical ectopic pregnancy from 40% to 10%. When performed before 10th week of gestation it allows early diagnosis and effective interventions to reduce risk of bleeding and death and maintain reproductive capacity of women.8 Transvaginal ultrasound criteria described by Timor-Tritsch for diagnosis of cervical ectopic pregnancy.9 The criteria includes (i) presence of gestational sac or placental texture dominantly within the cervix; (ii) absence of intrauterine pregnancy; (iii) visualization of an endometrial stripe and (iv) enlargement of the cervix. It is important to differentiate, based on findings of imaging, between a spontaneous abortion in the passing, a true cervical ectopic gestation and a scar pregnancy. A spontaneous abortion in passing may present with bleeding accompanied by pain whereas cervical pregnancy mostly present as painless vaginal bleeding. Absent cardiac activity with sac located centrally in uterine cavity and presence of “Sliding sign” (gestational sac slides against the endocervical canal in a miscarriage when pressure is applied to cervix with probe but not in pregnancy implanted in endocervix) indicate spontaneous abortion. Gestational sac of cervical ectopic pregnancy is typically located centrally in endocervical canal below the internal os with cardiac activity present and peritrophoblastic blood flow on color Doppler along with absent sliding sign. Scar pregnancy can be differentiated by usg in which there is empty uterine cavity and cervical canal and gestational sac developing in anterior portion of lower uterine segment and absence of intact myometrium between urinary bladder and gestational sac. In our case, there were all features compatible with cervical ectopic pregnancy and she had not underwent any previous scar producing uterine surgery that rule out scar pregnancy. 3-D sonography provides an additional coronal plane that help to delineate the extent of infiltration by conceptus). MRI can be used as they provide better tissue characterization.

Treatment options include (1) Tamponade with foley catheter which is used mostly after other techniques like curettage. (2) Reduction of blood supply which may be done by cervical cerclage, vaginal ligation of cervical arteries, uterine artery ligation, internal iliac ligation and angiographic embolization of the cervical, uterine or internal iliac arteries. This is mostly done prior to surgical therapy like curettage or along with chemotherapy as a conservative treatment. (3) Surgical excision of trophoblastic tissue which traditionally involves curettage and hysterectomy. Curettage offers conservative treatment whereas hysterectomy may be required for intractable haemorrhage, 2nd or 3rd trimester diagnosis of cervical pregnancy. Some reviews show 100% cervical ectopic gestations beyond 12 weeks ultimately required hysterectomy. (4) Intra-amniotic feticide where USG guided intra-amniotic instillation of potassium chloride and/or methotrexate. (5) Systemic chemotherapy which most commonly uses anti-metabolite drug methotrexate in single or multiple doses. (6) Local hysteroscopic endocervical resection to remove cervical pregnancy with/without laparoscopic uterine artery ligation. Systemic chemotherapy with methotrexate requires prolonged treatment and poses maternal systemic toxic effects. Presence of fetal cardiac activity is a relative contraindication to its use and also may affect the fetus of subsequent pregnancy. Limited studies suggest potentially harmful effect on ovarian reserve.

In our case, we opted for endocervical curettage after discussing with the patient as she was nulliparous and desirous of future pregnancy after explaining all associated risks to the patient and her family. Keeping in mind the emergent need for hysterectomy and blood transfusion, prior written informed consent for both were taken and two units of blood preserved in advance. Setup for laparoscopic uterine artery ligation with hysteroscopic resection of product of conception was kept standby. Fylstra et al. have shown that 13 consecutive first-trimester cervical pregnancies were successfully treated with suction curettage using a cervical canal balloon.10 Dilatation and curettage is minimally invasive and effective treatment option in early gestational age when trophoblastic tissue has not very deeply infiltrated the cervical wall.

Prostaglandins have benefits that help in cervical priming before cervical instrumentation, it has effect of vasoconstriction that may help in achieving better hemostasis and also reduce requirement of additional hemostatic suture placement and other compression methods. Besides, it provides a non cytotoxic drug option before surgical therapy. Endocervical curettage performed after intramuscular administration of prostaglandin may allow full therapeutic effect of spontaneous abortion. There are very few reports using prostaglandin in treatment of cervical pregnancy like Postawski et al. treated using combined methotrexate, intra vaginal misoprostol and hemostatic sutures with foleys catheter tamponade.11 Spitzer et al. used local intracervical instillation of prostaglandin following curettage to prevent severe haemorrhage.12 Dall et al. used intra amniotic and systemic prostaglandin to achieve cervical ripening and simultaneous curettage which finally ended up in hysterectomy due to intractable haemorrhage.13 S Chew et al. described the use of systemic methotrexate and prostaglandin for management of cervical ectopic pregnancy.14

Conclusion

This case report demonstrates the high incidence of cervical ectopic gestation in patients with previous history of repeated curettage, causing injury to the mucosa and favouring ectopic implantation, along with known risk factor of artificial reproductive technique like IVF in our case. Ultrasound diagnosis in early pregnancy is very essential to avoid catastrophic consequences. Our case shows the use of a simple yet effective treatment technique by endocervical curettage after administration of prostaglandin intramuscular which minimizes the requirement of reduction of blood supply before the procedure. It may also obviate the use of methotrexate and its prolonged follow-up and maternal systemic side-effects and on subsequent pregnancy.